REGINA -- In recent history, it was customary for schools to force Indigenous children to cut off their hair, robbing them of their braids which served as a strong cultural symbol -- one that wove identity, ancestry and pride together.

Historically, Western society has not empowered the cultural expression of Indigenous and Black people of colour. In the second of this two-part series, CTV News will explore the complex personal journeys some in Saskatchewan have embarked on to reconnect with their cultural identity through their hair.

"IT FELT LIKE THEY WERE TAKING AWAY A PART OF ME"

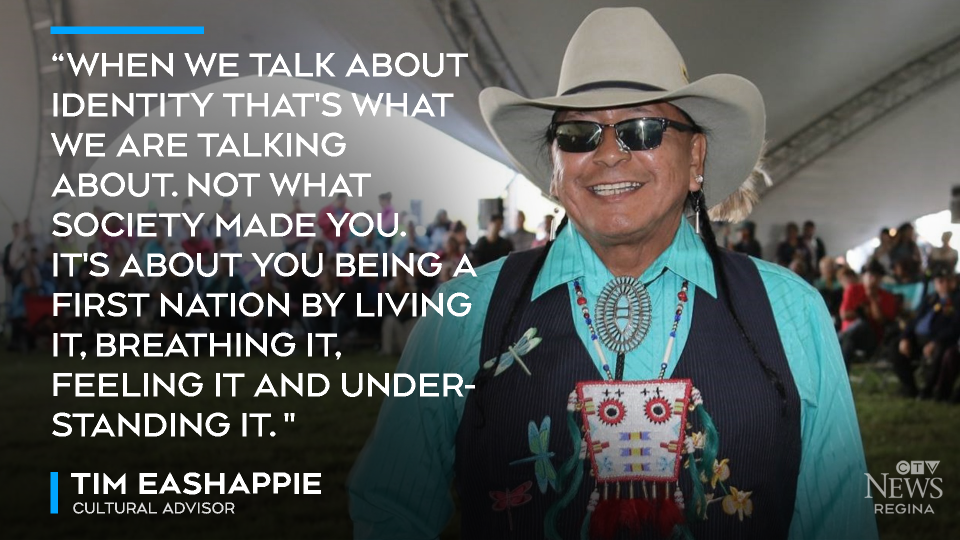

Tim Eashappie, from Carry the Kettle Nakoda Nation, learned directly from his grandmother just how significant long hair is in Indigenous culture.

"My grandmother used to tell me, 'Grandson grow your hair, keep it long, that is your connection to Mother Earth,'" Eashappie said. "It's your extra-sensory feeling for everything that is out there."

But just like so many in Eashappie's generation, he was forced to go to a residential school as a child and his braids were taken away.

"I was ordered in to go get my hair cut," recalled Eashappie. "It felt ugly, like they were taking away something I was so proud of."

Year after year, every time Eashappie would start a new grade of school, his hair was cropped short.

"They were stripping me of that culture, teachings that I was told when I was young. That's how it felt. It felt like they were taking away a part of me."

A SACRED SYMBOL

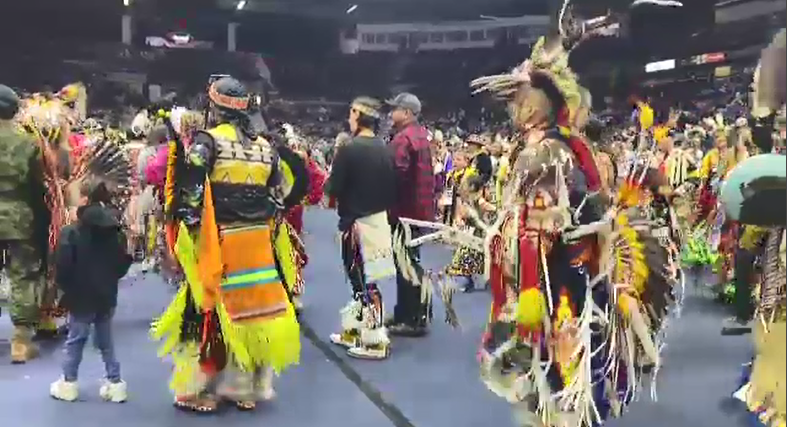

While the braid comes first to mind for many when thinking of Indigenous hair, the hairstyles worn through history vary tribe to tribe.

"When [hair] was parted down the center, that was the Nakoda, Lakota, Dakota way," explained Eashappie.

Bangs and shaved parts of the scalp were also commonly used to distinguish different groups and where they came from.

Hair that was worn down or out was a sign of a warrior ready for battle, while braided hair signified peace, which is why it's so commonly seen at a ceremonial Pow Wow.

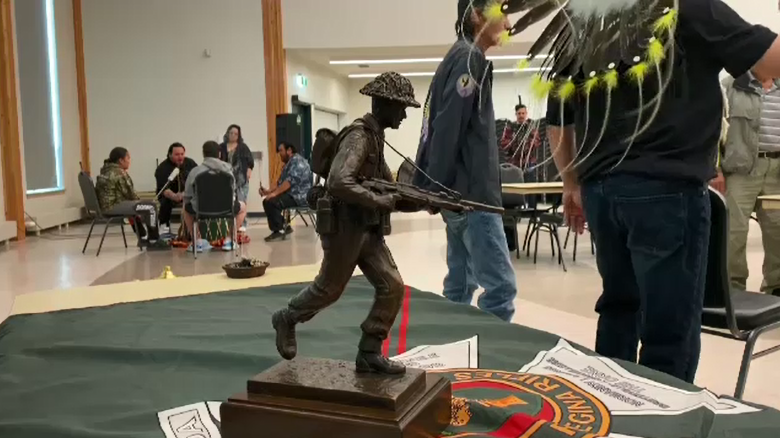

The symbolic power of the braid was put on full display in September 2020 on the front steps of the Saskatchewan Legislative building.

After a nearly 600 km journey on foot from La Ronge to Regina and weeks of fasting, Tristen Durocher had his braid cut off to mark the end of his ceremonial fast that was bringing awareness to the alarming number of Indigenous suicides in northern Saskatchewan.

"His journey was done. His hair was a symbol of coming all the way home to Regina and he came for a reason and as he fulfilled his obligation, he cut his hair. That way when he burned it and started walking, he started a new life," explained Eashappie.

LOST AND FOUND

Jennifer Dubois grew up in Regina but her family has a long-standing connection with the George Gordon First Nation. Growing up, hair and it's significance in Indigenous culture wasn't a discussion in the household

"I don't want to say [my parents] weren't proud, that's not the word I want to use, but they never really focused on the culture," said Dubois. "They were in that generation of having to hide it, having not to embrace it."

Once Dubois met her husband though, her eyes were opened to parts of her culture she never had known before.

"I just wanted more. Like, I just craved it. I loved everything I was learning," said Dubois.

Jennifer Dubois with her husband and their two children (Supplied: Jennifer Dubois)

Her motivation would lead her to eventually opening her own hair salon in Regina, Miyosiwin Salon Spa. Miyosiwin meaning "beauty" in Cree.

All her staff are Indigenous and her services are catered for clients of all hair types, but Dubois knew there was a void in the community when it came to Indigenous hair and beauty.

"For me, that's when I realized this was my passion," said Dubois. "I want to open a business that shows Indigenous culture in a positive light when it comes to hair care."

KEEPING TRADITION LONG AND STRONG

The stigma surrounding long and braided hair still exists in todays society, especially when it comes to what is and isn't professional in a workplace setting.

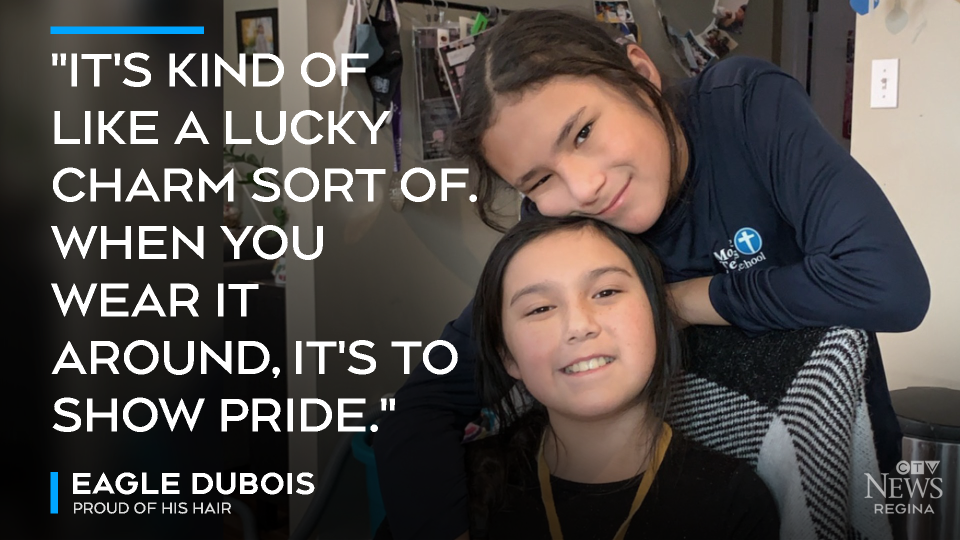

Bullying also persists, commonly for young boys in school who wear their hair in braids. For Dubois, she has empowered both her son and daughter to be proud of their hair, but she admits it hasn't always been easy.

"It's something as simple as just sitting in a restaurant and the waitress asking, 'What would you like dear?' referring to [my son] as a girl even though I have two kids."

Thirteen-year-old Eagle Dubois takes it in stride though, a possible sign that today’s youth are starting to outgrow the stereotypes surrounding Indigenous hair.

Jennifer Dubois with her son, Eagle (Supplied: Jennifer Dubois)

"It's kind of a lucky charm sort of," Eagle said when talking about his long braided hair. "When you wear it around, it's to show pride."

Eashappie also is encouraged with how the next generation is starting to normalize different styles of hair, with several of his own grandsons wearing their braided hair with pride.

"I'm so proud of all the young people for doing this because this is their identity," said Eashappie. "When we talk about identity, that's what we are talking about. We are talking about who you are. Not what society made you. It's about you being a First Nation by living it, breathing it, feeling it and understanding it."