REGINA -- Doug Campbell says he could tell there were serious issues in his daughter’s marriage that she was trying to downplay.

“She would tell us stuff when she was drinking, their problems and she would take off on him,” Doug said. “But when she came home she would say ‘it’s no big deal I can handle it’ and she would try to dismiss it.”

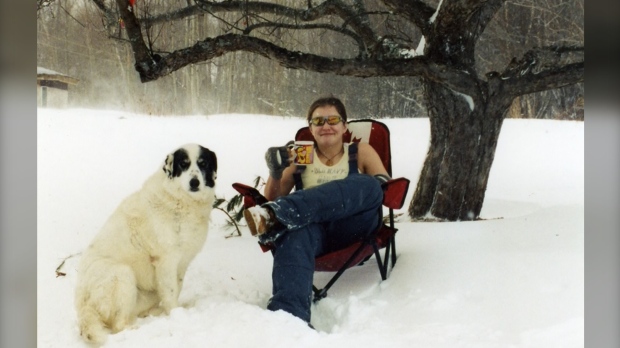

Jenny McKay was 33 when she was murdered by her husband, Jason, in September 2017. Jason was convicted of second-degree murder after a trial that shed a light on a history of domestic violence.

Jenny’s situation is far from an isolated incident. The most recent report from Statistics Canada on intimate partner violence (IPV), which cites police reports from 2017, shows that the rate of IPV in Saskatchewan is more than twice the national average, which is 313 victims per 100,000 people.

Saskatchewan sees 682 victims per 100,000 people.

Some cases of IPV end in intimate partner homicide, with 476 victims in Canada from 2010 to 2015.

PATHS (Provincial Association of Transition Houses and Services of Saskatchewan) is a local organization that researches and educates about domestic violence in the province.

According to PATHS, control is one of the most visible warning signs for escalation of violence.

Control

“When someone is regulating aspects of their partner's lives, controlling who they talk to, controlling if they are able to see friends and family and their work. That is a very serious red flag and is often present in situations where someone can be killed,” Crystal Giesbrecht, Director of Research and Communications at PATHS said.

The presence of control in the McKay’s marriage is something that Jenny’s family is aware of.

“Her behavior was very typical for someone in a domestic abuse situation,” Doug said. “Women in these situations are afraid, confused, they don’t know where to turn.

“When everything is controlled by someone else, you have no way out.”

Court heard that Jason and Jenny had a shared email address. The Crown argued that when Jenny began setting up viewings to rent her own place, Jason would intercept the email correspondents and sabotage her chance at securing a new home.

“We still didn’t know everything that was going on, she was trying to protect us from it,” Doug said.

Warning signs

Police attended the McKay home three times on Aug. 27. 2017, just days before Jenny’s death.

Const. Correy Wood with the Regina Police Service attended the home in the 200 block of Angus St. for a domestic call. Jason’s daughter testified that he pushed her, prompting an altercation with Jenny that resulted in her calling police.

Wood testified that Jenny told him that her relationship with Jason was abusive and she was working on a plan to leave.

That night, Jason was transported by police to his mother’s house by Const. Jeremy Kerth.

“F***g chicks are crazy. It’s over, [Jenny] called the cops on me I’m not abusive. I’m just stern. I’ll smack her right in the head for being stupid though,” Kerth testified Jason said to him.

That same night, Jenny told a 911 operator that she believed Jason was going to kill her.

Giesbrecht says that when a victim of domestic violence expresses fear, it’s important to listen.

“When someone is afraid of their partner and states that they feel their partner could kill them, that’s something we need to respond to and take very seriously,” she said. “People may downplay and they may cover it up but people in these situations usually know their partner best.”

Steps for family, friends

Jenny and Jason lived in Regina, far from Jenny’s family in Nova Scotia.

Doug said that after a while, Jenny was homesick and missed her family.

“She didn’t come home much, and that kind of bothered us,” Doug said. “We didn’t really know why, we thought it was about money but I think it was more about other things.”

Jenny’s family, her father Doug, mother Glenda and sister Ally, told CTV News Regina that they saw some red flags, but their ability to intervene was challenged by distance and time.

“The last couple weeks, we knew she was trying to leave [Jason], and we were encouraging her to leave,” Ally said. “I knew toward the end it wasn’t good, but I never would have imagined that something like this would happen.”

Giesbrecht said it’s not uncommon for loved ones to have concern, and not know what steps to take to address the sensitive situation.

She advises that in order to support someone who may be experiencing IPV, learn more about the services in your community.

“Encourage them that they can reach out, even if it’s just over the phone,” she said. “Let them know that you care, that you believe them and that you’ll be there to help them figure out what they need. Showing that support may help someone trust that they can come forward and see positive results.”

Resources

Giesbrecht said that the most violent and dangerous time for a person is once they start planning to exit a violent relationship. She said this is when it is crucial that supports are in place for victims of IPV.

211 Saskatchewan Services for People Experiencing Violence & Abuse provides a directory of services in your area for people experience IPV. These resources exist to help those experiencing violence and abuse.

For a list of all domestic violence shelters for women across Canada, click here.

Shelters can be contacted anytime over the phone to provide support and assistance to those trying to leave a violent relationship.

The First Nations and Inuit Hope for Wellness Help Line offers immediate and culturally aware phone-based crisis intervention at 1-855-242-3310.