REGINA -- While working on her latest exhibit at the MacKenzie Art Gallery, Divya Mehra discovered that a small stone statue was stolen in 1913 by the gallery's namesake, Norman MacKenzie.

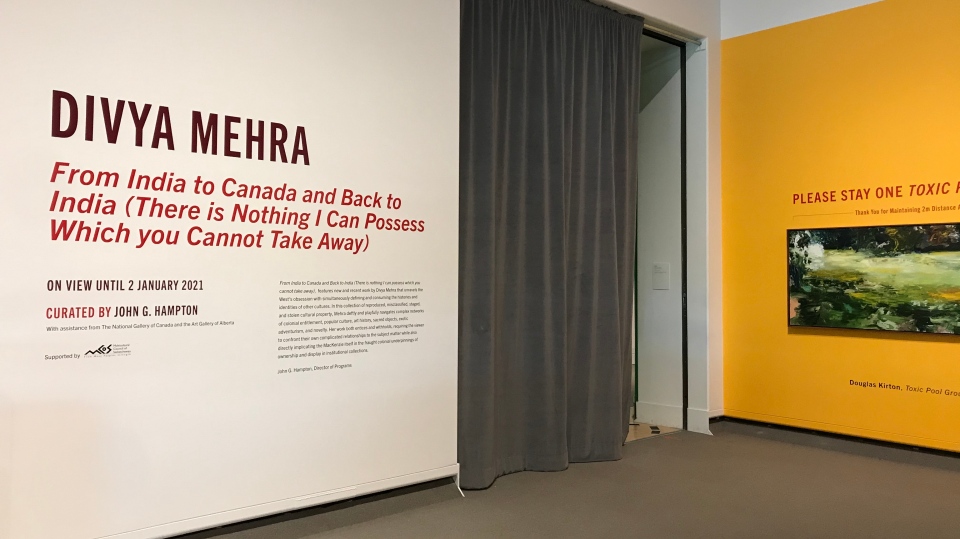

Mehra's exhibit is titled, From India to Canada and Back to India (There is nothing I can possess which you cannot take away).

"She was going through our archives and found this really enthralling and upsetting story about an object in our collection which had been improperly obtained or stolen on behalf of our galleries namesake, Norman Mackenzie," John Hampton, the CEO of the MacKenzie Art Gallery, said.

The statue, part of the University of Regina's collection, is being held in trust and stewarded by the gallery.

Hampton said documents written by MacKenzie indicated the statue was taken from Banares, India in 1913, while MacKenzie was there.

"MacKenzie believed that he had acquired a sculpture of the Hindu deity, Vishnu, and it was subsequently catalogued as such. This misidentification was corrected in the fall of 2019 when Mehra, recognizing that the clearly female figure was not Vishnu, reached out to Dr. Siddhartha V. Shah, Curator of South Asian Art, Peabody Essex Museum who revealed that the deity depicted was in fact Annapurna, also known as the Queen of Benares," the gallery said in a release.

The statue, part of the University of Regina's collection, is being held in trust and stewarded by the gallery. The university and gallery are working to engage in conversations with the Indian Government about the statue. The university and gallery are willing to return it to India if the government accepts.

"As we look at what our mission is as a gallery on how we represent culture, it's important to us that we represent it in a responsible and accurate way and that requires having the buy-in of voices of the people whose cultures were representing," Hampton said.

The exhibit's walls are painted a bright green and has four main focal main points in the room.

One point features a brown bag of sand that represents the stolen statue that now sits in the gallery's vault.

The second area contains a book with information about Norman MacKenzie taking the statue from India.

The third area has an inflatable Taj Mahal replica and the fourth area contains an inflatable replica of a book titled, Orientalism, by Edward W. Said.

This statue has sparked the gallery's first-ever deaccession review, meaning it wants to find the rightful owners of the statue and return it to them.

"For her project, Mehra stages an intervention into the permanent collection, performing a conceptual heist that deftly and playfully addresses the practices, ideologies, and legacies of collectors and benefactors of the early twentieth century," the gallery said.

David Garneau, a professor of Visual Arts at the University of Regina, said this statue is one of many pieces of art in museums and galleries that were wrongfully obtained.

"Certainly 100 years ago, the ideology was that the dominant white folks had access to everything in the world for their museum collections because they were the top of an ontological hierarchy of power and knowledge and that the whole world was in their domain and they took the best things from everywhere in the world for posterity for education for all these things," Garneau said.

He added it's just as important to restore relationships as it is to see if the country wants the piece of art returned.

"Under colonialism, because trading relations were uneven for some objects, there's sort of a moral imperative to return them because they have greater meaning and importance with the people that they originated with so that it becomes difficult," he said. "In the case of this is a religious object, if there's goodwill to want to return it and the people want it back. That's the key. So it's all about a relationship, rather than just doing a seemingly right thing."